|

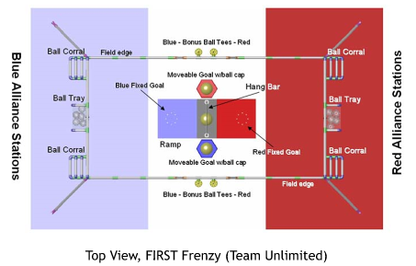

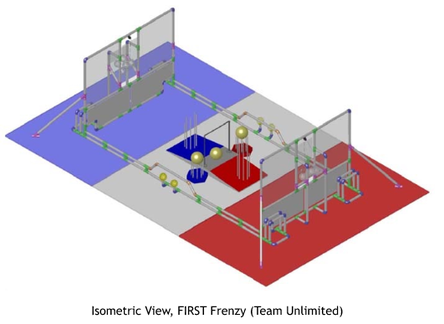

As Ladies in FIRST we’ve all had some crazy “firsts”. The first time going to a competition. The first time getting up in front of the judges. The first time meeting your team. The first time BUILDING A ROBOT! But have you ever thought about what it would be like to be the first to start a program within FIRST? I have been one of the very few to have that unique opportunity. My FIRST career as a team member took place between 2001 and 2009. At the beginning of that time, the FLL program was just kicking off. But by the time my all girls team and I had reached the end of 8th grade (the end of the FLL program in the US) we were hungry for more. We had joined our “brother” team in Atlanta at the World Championships in April 2004 and had seen the “big robots”. As many of you know, after seeing an FRC team in action there’s no going back. But we had our share of obstacles. Mainly, we were not funded or supported by our school district. While they loved what we did and championed our STEM cause, there was no space for an FRC team and no faculty willing to put in the time or resources. As a “potential” naïve rookie team, we had no space, no funding and no mentors. Like many FLL teams that had come before us, we thought that our robotics days were over. On to sports, theatre and homework. Or was it? By late January-mid February of 2005 our group got the news. Now when I say our group, this is something VERY unique. My town has approximately seven or so FLL teams each season that all work under one organization. They meet together weekly to talk about problems, show off their robots and have fun! So our new group of engineers consisted of members from an all-girls team (grade 8), an all-boys team (grade 8) and an all-boys team (grade 9). These teams then mixed together to create two NEW teams to compete in our new challenge. Why did we do this? Our town’s organization was only offered two slots in the pilot program demonstration in Atlanta. We also wanted to mix things up, since team members had already spent the FLL season with each other. With a completely new challenge we had no idea what to expect. There needed to be an equal amount of builders, designers and programmers on each team. Our two teams sat wringing our hands for a while. The only information that we had been given was that it was to be a “scale FRC event”. With that in mind, we thought: “shoot, we know NOTHING about building and designing an FRC robot”. So we had boot camp. Boot camp included everything from engineering basics (ie what’s a center of gravity) to how to code in C+. We were very lucky that all of the dads/coaches on our team were either engineers themselves or worked in software. With the basics under our belt, we finally received our kits and the challenge on March 22, 2005! The First Vex Challenge (FVC) was designed (and continues) to be a stepping stone to the FRC program. Because of its intended purpose, the first year challenge was a scaled version of a previous FRC challenge (FIRST Frenzy: Raising the Bar). Like play today, the challenge started with a 30sec autonomous portion and a 2 minute driver portion. Each team had to drivers and a human player, similar to FRC play. By removing a small yellow ball from the side of the field during the autonomous section, the balls were released from the ball trays (these were released regardless after the 30 second mark). The object of the game was to try to shoot balls into your alliance’s moving or standing goal. Bonus points were awarded for “capping” a goal with a large yellow ball or for hanging on the metal pole in the center of the field. We had four main challenging areas: building, testing, and programming (as any FIRST team can attest to) and the notebook. Building wise - none of us had ever made a robot out of metal. There was wiring to deal with, the construction of a robust chassis and CUTTING metal with a hacksaw (my new favorite). One of the interesting rules that was thrust upon us was that teams could ONLY use what came in the VEW box. Not only was the “measure twice cut once rule” enforced, but prototyping and brainstorming became a much more integral part of the design process than in FLL. Testing and running the robot was another main issue. An FLL table easily fits on most kitchen or dining room tables, or even the floor. The FVC arena was massive in comparison. There was no way it could be built, there was nowhere to put it! The only items that we were able to build (from scratch) were the ramp/platform with the hanging bar that sits in the center, and a moveable goal. In terms of practicing for a full scale tournament we were in tough shape. Software wise, I think we tried to keep it simple. There was not much that could be accomplished during the autonomous portion of the game, but like many teams, ours tended to leave programming until the last minute. Another new aspect was the engineering notebook. As this is not a part of the FLL requirements, no one really knew where to begin. The only items called for in the FVC engineering notebook were the basic tasks and reflections sections still in use today, with any blank or “deleted” sections crossed out with initials. Seemed easy enough. Assigning a team member to write in the notebook, now THAT’s a different story! Like many teams, there was a trial and error period. But with only 6 weeks and a brand new kit we had a steep learning curve. What wheels would work well on the playing surface? What was the right strategy? What gearing should we use? Are we going for speed or torque? Do we even want to hang from the middle bar? Who on our team is good and accurate at throwing whiffle balls!?! One of the teams was able to attend a scrimmage at WPI with other FVC demo teams on April 9th 2005, just two weeks before the World Championship. What a game changer! After designing for a month without a full scale field and without having a working knowledge of how a match would actually run- their experience was incredibly valuable. With pictures and stories in tow, both teams were able to redesign their robots in the following two weeks for the Championship. A tournament can be a daunting place. Add on the additional pressure of it being the Worlds Championships (held in Atlanta). Add on the additional pressure of having never competed with your robot before on real playing field. You start to wonder if you should even be there… But as anyone will tell you, it’s an amazing experience. While only one team of the two teams made it through alliance selection and neither team won any awards, we all had an amazing experience showing off our creations. By the start of the 2005-2006 season in September we had created a total of three FVC teams stemming from the old FLL teams, and we never looked back- with at least two thirds of the teams returning to the World Championships each year until high school graduation. In writing this piece, I contacted my team members (OF COURSE) to get their opinions on FVC and the move to FTC. One member pointed out the “VEX” is a much cooler name than “Tech”… but oh well! However the most common observation by my team members was in regards to the move to the new FTC kit in the 2008-2009 season. While game strategy and play remained the same, the Tetrix kit was a curve ball to teams that had become accustomed to the VEW kit. Tetrix kits were provided to teams that had already been involved with FVC, and our team took advantage of what we saw as “free metal”. The main change was the move from plastic gears and components to aluminum. This was received enthusiastically by our teams, as the plastic components (especially the gears and the tank treads) had a tendency to break very easily during competition. During the FVC years, it was not uncommon for a robot to die during a match because of a broken gear or wheel; many “spare parts” were often found on the field. But with “free metal” came a major challenge: the parts rarely matched up. VEX metal aligned with VEW metal and Tetrix metal aligned with Tetrix metal, but the two rarely fit together. As teams today know, the Tetrix piecies have a circular hole pattern. The vex pieces, on the other hand, had a simplistic square hole pattern. This created major problems in our design, and cost the team valuable build time as we sometimes found ourselves trying to put together pieces that didn’t quite fit. But in the end everything works out for the best… I am so thankful for the opportunities that the FVC and FTC programs have given me. By allowing teams to partake in a competition that does not need major funding or a large workspace FIRST allowed middle and high schoolers to pursue their love of technology and their love of the game. Every student on the three teams from my town during the pilot years either pursued a degree in a STEM field, is working in a STEM field, or took a course in STEM during college (just for fun!). We had a blast during those five years creating friendships, making memories, and building robots, and I can only wish the same to all the other teams. Best of luck to the all FIRST teams this season! Team Unlimited. “Our 2005 Spring FVC team activities in photos.” Sharon Youth Robotics 2013. 2 October 2015. <http://www.syraweb.org/eaglevex/Photo2005spring.htm> Gawle, Julia. “Robotics.” Facebook. 8 March 2009. 3 Oct 2015. <www.facebook.com> This blog was writeen by Michelle Parziale of FIRST in Alabama. If you are interested in blogging for FIRST Ladies, click here to sign up on the schedule.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Be a guest

Do you want to be a guest blogger for FIRST Ladies? You can write about a topic of your choice! Anyone can submit a blog, especially our Regional Partner teams! Please email us the a Google Doc of the completed blog. Thank you! Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed